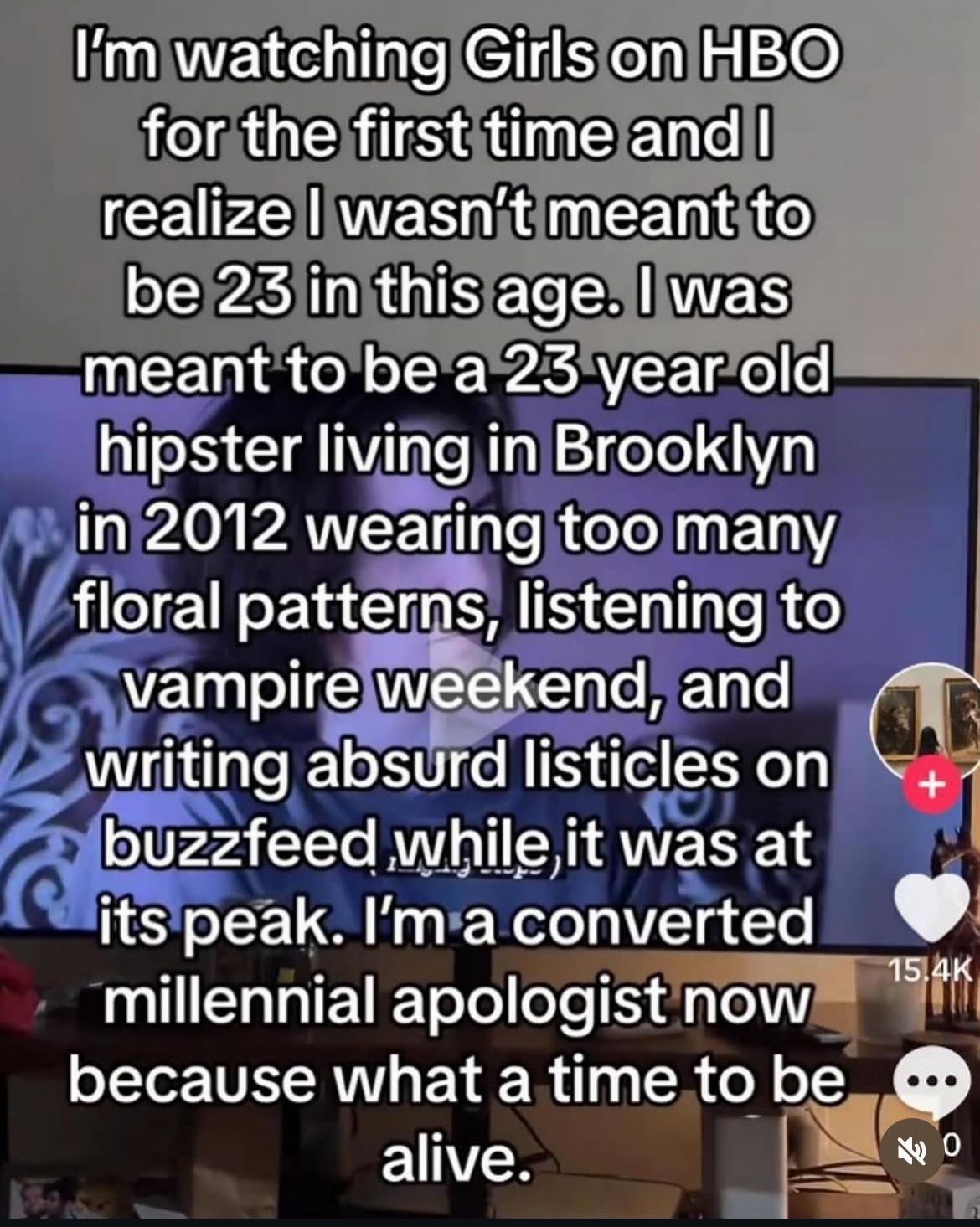

There’s a screenshot from TikTok that recently caused me and a group of my writer friends to lose our minds.

“I’m watching Girls on HBO for the first time and I realize I wasn’t meant to be 23 in this age. I was meant to be a 23 year old hipster living in Brooklyn in 2012 wearing too many floral patterns, listening to vampire weekend, and writing absurd listicles on buzzfeed while it was at its peak. I’m a converted millennial apologist now because what a time to be alive.”

True to the spirit of that era — the screenshot lacks attribution

This is my actual lived experience, described by someone who was apparently born before or around 9/11. There are only two elements of this description that do not apply to me: I was 23 in 2013, and I stopped listening to Vampire Weekend after they released Contra.

For the few of us who lived that life, it was an inspiring time to be alive. Media startups were abundant. Young writers like myself who were willing to work for $36,000 dollars per year (in New York City) were allowed past the gates kept by legacy media and the traditional career path of working at a local newspaper to climb the ladder.

We were people with limited experience who were given large platforms and freedom to experiment with form, subject, and voice. It felt, to quote Tony Soprano in the pilot episode, like it was “good to be in something from the ground floor.”

But the best is over.

My early resumé reads like a parody of someone who worked in this business beginning in 2014. My first role in journalism was in the early days of BuzzFeed News. They hired me as an intern on the sports desk — then dissolved the section on the second day of my internship.

There, I learned how to do journalism. Seriously, my only consistent writing experience was writing, uh, pieces similar to this on Tumblr and being a highly opinionated person on Twitter. I blasted off my opinions on sports and everything else without even a moment of hesitation. This was one way young writers got hired in those days: You built up a personal brand, got noticed, and someone gave you a chance.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Critical Thinking to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.