1/9 When I permanently deleted my Twitter account, there were nearly 100,000 people and bots following me. A whole random mid-sized American city had at one point elected to subscribe to my thoughts and links to my news articles.

2/9 A website that had consumed and allowed me to chronicle my life for 15 years disappeared. I didn’t care. I had ridden the wave of its good times and toxic times and was simply done.

3/9 People who didn’t use Twitter regularly or only knew of it through its presence in news media likely don’t understand that the site was once a radical place that changed the conventions of critical thinking. It was largely a force for good, which seems difficult to recall now.

4/9 Eventually Twitter became a website for fighting, not critiquing. The userbase and society as a whole fractured and became politically and socially segregated. Even before Elon Musk bought it, the whole thing had become a mess.

5/9 Disinformation, cults of personality, combativeness made it a miserable place. Then Musk drove it into the ground. Let that sink in.

6/9 There was once a better, more expansive internet. I was there. Twitter was once an easy way to make dumb jokes with people you’d never meet in the real world. It was a prosocial place, until it became the epicenter of antisocial behavior. I don’t miss it, but I do reminisce.

7/9 I was a Twitter power-user. The userbase data on Twitter was always really funny. A lot of people started accounts and forgot about them. Something like a few thousand people actually actively used the site every day. I wasn’t content to lurk, though. I was a true poster.

8/9 Everyone who used Twitter between 2008 and 2020-ish has their own story about its utility and detriments to their lives. Overall, being on Twitter in those early years was incredibly good for my career and the trajectory of my life.

9/9 Behind the tweets though, it was a disaster for my sanity and brought out the worst in me. Here’s how I experienced Twitter. Rest in peace. Or piss. I can’t decide.

In 2010, I was a 20-year-old woman working retail for a luxury fashion brand in San Francisco. I did not have a college education, a financial support system, or any goddamn clue how I was going to find a career.

I was constantly on my phone during my shifts at the handbags and shoes store. I was reprimanded repeatedly. But while I was waiting for wealthy people to buy ostrich leather handbags (yuck), there were people online rapid-fire posting about what else was going on in the world.

All day, every day, people in San Francisco were posting on Twitter about the ticky tacky political dilemmas that plague that city, and media people in New York were posting news with a tone of self-importance. There were so many people, and you could just talk to any of them.

I grew up on the internet and have an extensive history of making real friends online. My use of Livejournal and Tumblr led me to an overly comfortable stance on posting about my life online. My internet upbringing taught me to be an open and authentic person in public forums.

So, when I started using Twitter, I just began posting about my life. I posted a lot about sports. I turned the men I was dating into fodder for mockery. And I flew off the handle about local and national politics.

I wasn’t thinking about my digital footprint at the time, or the ways my young adult opinions could be attached to my name forever. I just knew that it felt great to have a place to perform a curated version of myself.

Eventually, people my age graduated from their journalism undergrad programs. They entered the world of digital media as social media editors or bloggers. I lived in envy of them. To me, the coolest thing a person could do was be the social media voice for a fast food brand.

I owe my career to my relentless posting on Twitter. I made friends who were media-adjacent. Someone tweeted a listing for an internship at BuzzFeed News. The job was to write about the intersection of women’s issues and sports — two topics that were constantly on my mind.

My internship application was unconventional. I had never done journalism and had no clips. Instead, I created a Tumblr page where I wrote some blogs about feminism and sports. That was my application! “loved your application tumblr page,” the hiring editor wrote in his email.

I moved to New York City to take a $10 per hour internship. I kept posting, posting, posting. My Twitter friends became my real life friends. I learned how to write a news story and stumbled into a career.

All along the way, I kept posting, posting, posting. I blended the personal with the professional and nothing was off limits. I scrolled Twitter during dinners with friends. I prioritized the attention I got online.

At that time, I thought constantly about what I would post next. It was radical back then. Anyone could build an audience and an avalanche of perspectives that were new to me flooded my feed. Being on Twitter helped me expand my worldview and see beyond the bubble of my own life.

I learned a lot about racial discrimination on Twitter. Black women, such as Mikki Kendall, were posting constantly about their experiences and the concept of “intersectionality.” I’d either not heard Mikki’s perspective, or I hadn’t actually listened if someone had told me.

My practice of feminism changed, too. When Sheryl Sandberg said the word “bossy” was sexist, I was like “hell yeah.” Then, a bunch of women with a lot more life experience than me critiqued the campaign and pointed out that biases don’t change just because the language changes.

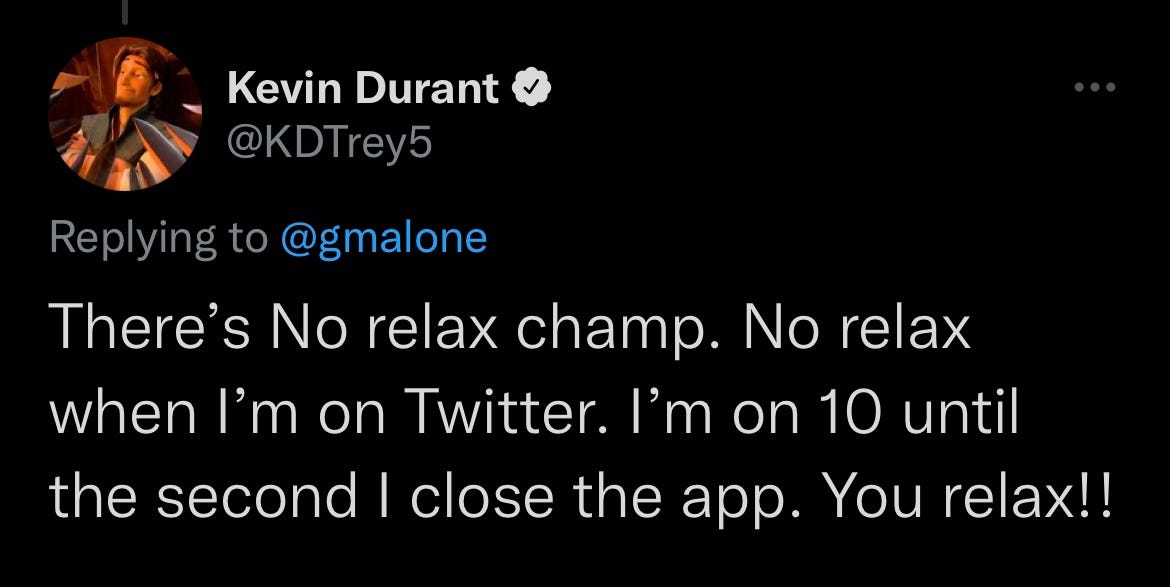

I learned new perspectives on Twitter, but I mostly spent my time firing off my own opinions and arguing with anyone — anyone! — who disagreed with me, a 24-year-old white woman from the suburbs. It was like playing an intellectual puzzle; the smartest poster wins.

At that time, there were few women covering pro sports. A few dozen (?) women worked on major sports beats, but women like me were breaking into the industry through the digital route. We were just sort of launching ourselves into the industry without a traditional track record.

People were really shitty to women who liked sports back then. Maybe they still are, but it was the dominant experience 10 years ago. We were always defending ourselves, every mistake was blown up to be a big example of disqualification. It was intense.

Intuitively, I fought back against that wall of sexism by exhibiting the parts of me that are cool, smart, and funny. A lot of my fellow young reporter friends stuck to posting their work, showing their professionalism and credibility on their own beats. That was not my approach.

I think often about how many of the women who entered sports media when I did wound up being personality-forward online. I strongly believe this was the convention at the time because if the men who watch sports wouldn’t trust us, at least we could make them see us as people.

It worked for me. People thought I was cool and began defending me against the creeps and assholes. The more self-righteous I was online, the more people bought into my schtick. People seem to gravitate toward anyone who has a strong opinion. That’s really scary.

At the same time, my journalism career was taking off. Twitter helped me gain a significant following — and it kept me in the “editorial liability” category with my employers. The way I promoted myself and my work was always provocative. I wondered why I always felt on edge.

When I began covering baseball full time — the Yankees specifically, no less — my relationship to Twitter changed. Until that point, I had just been Lindsey, a Writer and Poster. To Yankees fans, I was immediately the Yankee Information Machine. I hated it.

For nearly my entire life, I had used the internet to establish my individuality. Suddenly, my personhood was reduced to Yankeeland. Fans were confused — and put off — when I tweeted about normal person things. Stick to sports came back. It was a drag.

The way I used Twitter was different from the reporters around me. Many of those writers are (smartly) content to be information merchants in public and real people in private. I couldn’t distinguish between the two. I took everything personally because to me, it was personal.

I was a miserable goddamn person during my five years on the Yankees beat. It was largely self-inflicted. I fought with fans who didn’t understand my job. I was over-the-top defensive every time I was wrong. I took in feedback as if I were staring at the sun with dilated eyes.

At some point during my years on the beat, I checked my Twitter analytics to see my engagement metrics. I wasn’t aspiring for more growth, I just wanted to know what was happening. It said that I received something like 500 replies each day.

The mind is not made for that amount of feedback. Mine in particular is not made for that. I turned on every filter I could. But the waves of praise and conflict were really activating my emotions, making me feel alive. My emotions were controlled by that day’s tone of feedback.

My posting overshadowed my work. Nearly every time I went on a podcast, I was asked more questions about my Twitter posts than my actual journalism. It insulted me, though it was my own fault that readers paid more attention to my unhinged posts than my serious journalism.

At one point, a person I was dating said that when we argued, I made my points as if I were making posts on Twitter. Ouch. Sounds like I was concise and punchy. But it was fascinating and perceptive feedback, and it floats around in my brain to this day.

The moment it all went wrong for me was the day I went mega-viral. I became what was called the “main character” of the day over something stupid. A baseball team posted a photo of a young couple on a date and I said men should try harder than wearing basketball shorts on a date.

People latched onto it and went bananas. A lot of people just made jokes about how I must expect men to show up to dates in top hats. Those were embarrassing, but fine, have at it. But a lot of people became seriously, seriously, angry at me.

The worst thing you can do in that type of situation is to try to explain yourself, which is exactly what I did. I explained that I’m in my 30s and have different expectations. People called me a bitter cat lady and I responded with photos of my dog. I engaged with them all.

That stupid post, dashed off without much thought, was a turning point. It brought out the people who hate women and want to cry about reverse sexism. A fan recognized me at the ballpark and called me a cunt to my face. I couldn’t dig myself out and convince people to like me.

This moment actually changed me. There is a before and after I tweeted that men should make an effort to dress nicely for a date. It’s the moment where my internet self was fully ripped from my real self. It’s probably for the best, but I lost my mind.

The person that strangers described was just… not me. I have many flaws, but people created a strange parasocial version of me. It freaked me out badly. I started posting MORE stuff from my personal life to try to convince this army of haters that I am a real, full person, too.

I’ve seen other high-profile Twitter users try to do the same thing when their persona escapes their personhood. It doesn’t work and it makes people in group chats ask why no one in that person’s life is telling them to stop. Most likely, they’ve heard it and refuse to listen.

Getting off the daily baseball beat and going to a national newspaper helped me start the process of disconnecting from the Twitter hell-cycle. I didn’t have to give injury updates; the newspaper would disseminate my work. I didn’t have to be there, so I learned to stop.

I began living in the real world. I think now about how many days and nights I spent refreshing my Twitter timeline instead of being active in the real social life around me. There was a time when I was constantly checking Twitter when out with friends. They were, too.

So, Twitter’s diminishing relevance in my life and my online community doesn’t feel like a significant loss. There were salad days on Twitter, but my own usage habits were unhealthy even back then.

I realize that I’m speaking about Twitter the way a substance abuser talks about their vice of choice. I don’t think there’s a general difference. I was addicted to dopamine and whatever hormone causes constant rage. There’s no Twitter rehab, but Elon did inspire a rapid detox.

The thing about Twitter that actually does upset me is the way it changed from a prosocial environment to an outrageously antisocial culture. A place I once considered a resource for expanding my worldview became a place for siloed opinions and perspectives.

Although I deleted my Twitter account, you can’t take the posting spirit out of the poster. I still love being active online. I love getting to talk to strangers and put my ideas out there and consume alternative views from strangers.

But I will never again spend entire days refreshing a social media app. I’ll never again check social media while on a date. I’m pretty sure I’m done having actual fights online. I can’t make the internet be what I want it to be, but I can choose who I want to be on the internet.

I just came to say you were really good at being a Yankees Information Machine, and I'm sorry my cohort made you hate it, and I miss having you on the beat, but you're also really good at this, so it's fine and cool.

It's funny... I kind of feel this way about blogging (oh man, the embarrassment of that time that included my unemployment and the rest... oh, the silliness of men in their 20s. at least in that time you had to first reach someone and then keep them interested. It was much less the randomness of discovery of a single tweet -- much like music was when I was in high school and college. I miss parts of those days, the connected feeling online when I felt less connected in real life. I honestly don't remember how long I did that blogging, but it seems much longer than it probably was and was a fraction of the time I spent on Twitter. While I feel nostalgic about early blog days (and blog rolls), I don't miss Twitter one bit. I Blue Sky some for work, but even that, I forget about most of the time. And, well, I haven't missed it