More Paul

By Alex Shephard

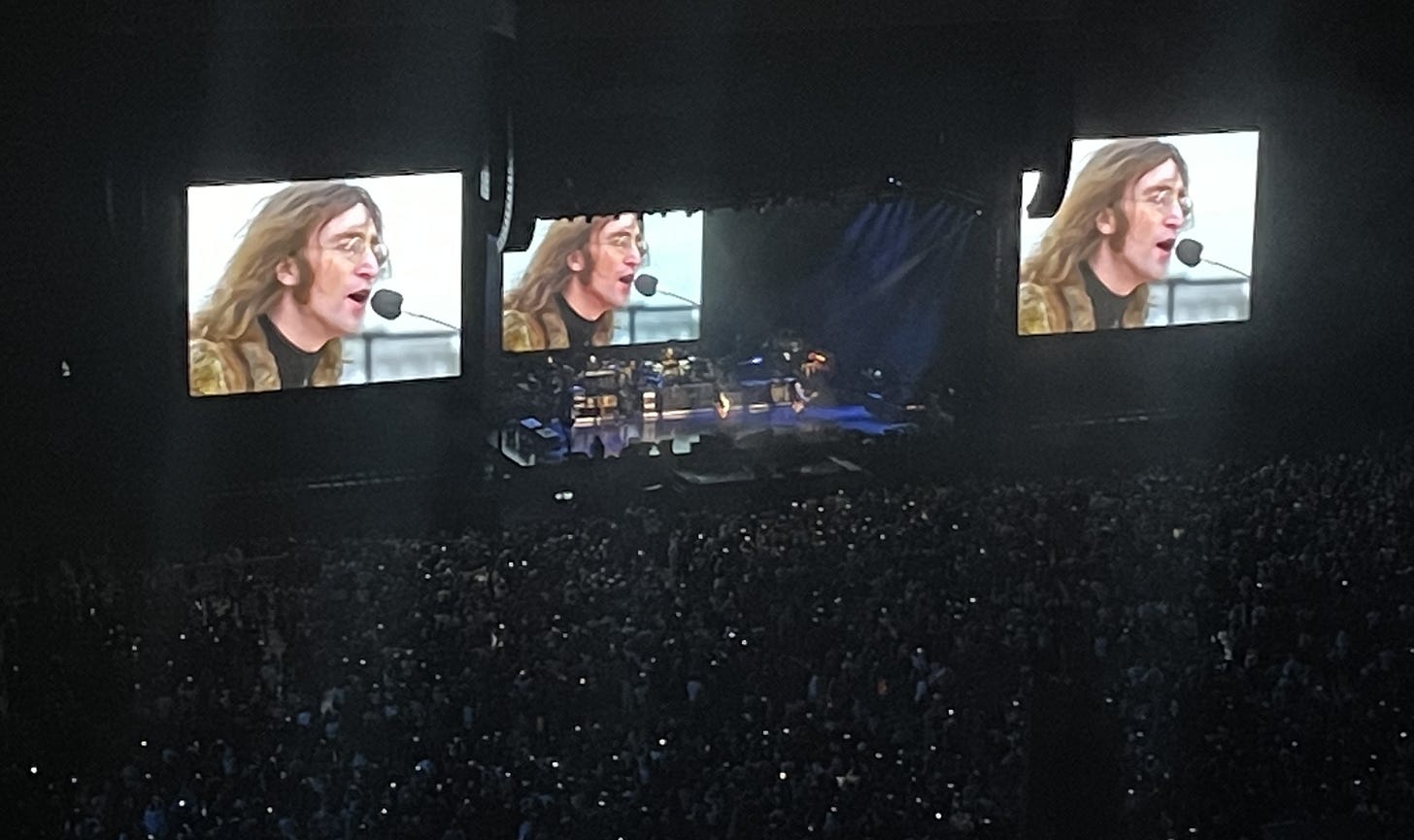

The last time I saw Paul McCartney, it was his 80th birthday. Jon Bon Jovi brought out a cake and led the audience in a rendition of “Happy Birthday”—before Paul, for whom nothing has ever or will ever be too on the nose, and the band burst into his own eminently forgettable “Birthday.” Bruce Springsteen had, minutes earlier, sat in on two songs I also don’t particularly care for—his “Glory Days” and The Beatles “I Wanna Be Your Man,” a song so mediocre they gave it away twice, first to the Rolling Stones and then to Ringo. It may have been because I had taken several hits of “Unicorn Spray”—a potent mix of LSD and ayahuasca—but it was one of the happiest nights of my life. What I really remember about it though, is that Paul tripped.

One of the best things about seeing Paul McCartney live is that he plays with a band. Everyone does, sure, but as something of a connoisseur of septa and octogenarian legacy acts, I am accustomed to bloat. As voices crackle and fade, the number of people on stage expands. Springsteen, for instance, now plays with a horn section and a group of backup singers, whose primary purpose largely seems to be to cover up the blemishes and croaks that accompany a 70-something year old voice. McCartney doesn’t do this. He still plays with something that can be described the way he often (somewhat gratingly) describes the Beatles: A little dancehall band. There are just five guys—which means the guitarist plays bass when Paul wants to play guitar and the piano player picks up a guitar when it’s time for “Hey Jude.”

It may have been after “Hey Jude” when I watched Paul stumble. He was coming down from the riser and got his foot wrapped around a mic cord. For a split second, you could feel 80,000 people holding their breath. Then Paul, in what can only be described as a Charlie Chaplin-esque pirouette, landed perfectly on his feet, arms aloft like the world’s oldest ballerina. He stuck the landing. He always does.

Here was an 80-year-old man about to do the thing all 80-year-old men do, perhaps the thing they do best, maybe even better than voting for fascists and nativists: Fall on his face. Instead, he did something with that strange mix of grace and good humor that has been there from the very beginning. “God,” I thought. “Even when he’s falling, he’s still the perfect showman.”

This is what makes Paul McCartney great and it’s also what drives people crazy about him: Even when he’s falling, he’s still somehow in complete control. There is, I suspect, a real Paul somewhere down there, but we almost never see it. There is nothing new or surprising about him and, if you discount his second marriage, there hasn’t been for several decades—and that may be charitable. Instead, we get the same charming stories told over and over again; we get the same persona that was there, already nearly perfect, when the Beatles first came to America. What you see is what you get with Paul. To be fair, what you get is quite a lot.

Still, I think it’s a mistake to focus so intently on the mask that Paul has worn unerringly for more than half-a-century and that it’s an even bigger one to assume that’s all there is. For one thing, that mask holds arguably the healthiest relationship to fame of any of his illustrious bandmates. If the graciousness with which Paul discusses fame can seem phony—and probably is—I find it no less irritating than George’s bitterness or the adolescent outbursts that characterized much of John’s public post-Beatles life. Ringo, self-aware, laconic, seemingly always cognizant of the fact that he is one of the luckiest people of the last century, has had his fair share of tantrums as well. Paul’s mask allowed him to live public life as a Beatle in a way that none of his bandmates quite could. But it is a coping mechanism as much as anything else. Persona, as Keith Richards writes in his memoir Life, is an effective way to deal with the weirdness that accompanies massive fame. (Ironically, Richards—perhaps the most persona-y rock star in history—meant it as an insult directed at Mick Jagger, who lacked the courage to deal with fame like a man (i.e. by getting addicted to heroin.)

In any case, yes, this means you get weird front facing videos under bridges. You get irritating conversations with Rick Rubin. You get what we’ve seen, for better or worse, since the release of Let It Be Naked: Paul attempting to manipulate his legacy and his band’s without ever really letting you in. You can contrast that with John, who was, you know, actually naked—literally on the cover of Two Virgins but also figuratively too for much of his post-Beatles life. Paul does not do nudity. Paul is always in control.

I am, if it’s not already clear, a skeptic of nudity, at least when it comes to art. I think Lennon’s displays of unvarnished reality—fuck the Beatles! fuck god!—are just as performative. In most cases, they also pale in comparison to Paul’s art from the same period. Paul’s best and most autobiographical solo album Ram, for instance, is far less direct than anything on John’s best and most autobiographical solo album, Plastic Ono Band. But I don’t think it’s any less personal. It’s certainly as good. And, for what it’s worth, the drop off from there is significantly steeper for John than it is for Paul. I think, moreover, that if you know where to look you can see the same trauma that John wore so openly in Paul. The persona is a way to protect him from a world that took his mother from him too soon also.

John’s loss—years after Paul’s—is always treated as something realer than his bandmate’s for a simple reason. His songs about his mother were directly personal (and, it should be said, oddly psychosexual). Paul, meanwhile, wrote “Let It Be.” Is that a less direct response to trauma than, say, “My Mummy’s Dead”? Sure. But it’s no less personal. It’s just more anthemic.

If I find the legacy building part of Paul’s final act irritating, I also think it’s defensible. If you are a Paul hater or even a Paul skeptic, history is on your side. For decades, Paul has been the “cute one,” the purveyor of silly love songs, the effervescent, bubbly counterpoint to the raw, genius that is John Lennon. John’s murder in 1980 not only cemented this simplistic depiction, it made him a martyr, someone whose legacy was not only unquestionable, but that also threatened to swallow up everything around him. The contradiction of John—as a figurehead for global peace and the embodiment of raw authentic art—was also expansive and it swallowed up the band’s other genius.

I do, for what it’s worth, think that John’s Beatles highs exceed Pauls, though one of the many great things about the Beatles is that a lot of the cliches really are true: They were always better together (and almost made each other better). But I think there’s good reason, even if it is a tad Machiavellian, for Paul’s recent turn toward legacy pruning. The public still undervalues and misunderstands his role in the Beatles and still, somehow, underappreciates his extraordinary legacy.

Part of that frustration comes from the same quality that frustrated his bandmates: He was a taskmaster and workaholic in a band with two, sometimes three, members who would often rather be doing something, anything, else. He was the only Beatle who felt that he had a responsibility to their audience, which took the form not only of producing amazing music at regular intervals but also to ensure that music was befitting of the world’s greatest and most popular band. I am not as fond of a lot of Paul’s later highs—“Hey Jude” is fine, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “Obla-di-Obla-Da” are a tad better than their reputation (which isn’t saying much), but “The Long and Winding Road” is one of the band’s ten worst songs—but I also vastly prefer his earlier work. It’s not an accident that the band’s artistic high point—the stretch from Revolver to Magical Mystery Tour—came immediately after Paul reached his zenith as a songwriter. John, for what it’s worth, got there an album earlier.

Still, the idea that John was on the avant garde and Paul was some dippy crooner couldn’t be more mistaken. It was Paul, not John, who had real connections to London’s contemporary art scene and it was Paul, not John—or even George, who he collaborated on Revolution No. 9 with—who was really enmeshed with the contemporary avant garde. This was, it’s worth underlining, the artistic avant garde’s high water mark in visual art and music and Paul—and not, it’s worth underlining as well, his bandmates—who was there every step of the way. Those crazy tape loops you hear on “Tomorrow Never Knows” were made by Paul in his girlfriend’s parents’ attic. That “orgasm of sound” that George Martin loves describing in “A Day in the Life” was Paul’s idea. Paul inhaled Stockhausen as a 24-year-old and, years later, when he hit an artistic wall, started experimenting with synthesizers. John just played Chuck Berry songs.

Most of all, though, I think the quality that irritates Lindsey is the same one that I love about Paul the most. At the end of the day, this is someone who I do not think could stop making music if he tried—even if he wanted to. What’s clear, even just listening to his bass parts on John’s songs (and a few of George’s later ones), is that melody just flows out of his pores. George and Ringo were there, for better and very rarely for worse, to make their songs better. Paul is notable in that he, with very few exceptions, made John’s songs transcendent. I can think of few, if any, instances in which the reverse was true. But that tells you quite a bit about the ways in which their, for lack of a better term, genius, was different. Paul is a musical genius. John is a genius, whose medium was music.

John was an artistic genius in a way that I think is easier to digest: His jaggedness and lacerating personality make him something recognizable—a tortured, artistic genius. There was something effortful about John’s artistic heights. All of those chords in “I Am the Walrus” are hard work. Paul is something otherworldly, someone who, like Mozart, produces music—produces art—simply by being alive. That his genius seems innate and, in some respects, uncontrolled makes it easy to discount. But it doesn’t make it any less genius.

There are many good jokes about the Beatles, but my favorite comes from the Simpsons. Bart has been brainwashed by Mr. Burns and his parents are looking for someone to break the hypnotic hold Springfield’s richest man has over their son. The deprogrammer they stumble upon has one standout bullet point on his resume: He, tells Homer and Marge, “got Paul McCartney out of Wings.” Homer, however, was not impressed. “You idiot,” he shouts. “He was the most talented one!”

For what it’s worth, the second best Beatles joke comes from the first season of I’m Alan Partridge and is also about Wings and also makes the same point. Talking to a young desk attendant at the hotel he is living out of, Partridge is shocked to discover they’ve never heard of Wings. Who are Wings? “They’re only,” Partridge says, “the band the Beatles could have been.”

Wings were not just uncool and insubstantial, they were a band beneath the dignity of someone who was in the Beatles. Nevermind, of course, that most of John Lennon’s 1970s output and everything that George produced after his debut solo album pales in comparison to, say, 1973’s Red Rose Speedway. John and George made several albums that hardly made artistic statements but, for whatever reason, people have always ragged on Paul for simply doing the thing he does best: Make music.

My opinion of Wings is, I will admit, a bit lower than Partridge’s. But I think the band is misunderstood for the same reason Paul is now. It existed as a vehicle for a man who can’t help writing songs and can’t live without performing them. What more can you want?

great read

I like the way Alex describes Paul’s genius here. It makes me think of Charles Dickens as an artistic analogue, who from what I know was a ruthlessly commercial workaholic and of course an unparalleled genius. But he was also criticized for being overly sentimental and lacking depth.

Anyway, thanks for these posts today, Lindsey! They were both great.