Enough Paul

Paul McCartney recently sat on the banks of the Arkansas River in Oklahoma and looked directly into his phone camera. The 83-year-old deity was recording an Instagram Reel to promote the show he was playing that night at an arena with a capacity of less than 20,000 people. It was the 66th show of his ultra-tour “Got Back.” My reaction was quick: “Go home.”

I’m not just a casual hater here. I respect Paul’s love of playing live (he says he was the member of the Beatles who tried to convince them to continue touring after 1966, though he admits now that his bandmates were right to retreat to the studio). I respect that he knows what his celebrity means to the 20,000 people who show up to see him wheeze his way through “Helter Skelter.” He has been creating art for more than 70 years and his drive for it still seems insatiable.

But I find it depressing, and quite gross, that the last decade or so of McCartneyism has consisted of him helping to spew out Beatles retrospectives that largely allow him to shape the lasting legacy of the quartet — and wring every dollar out of the story of his own life as he inches closer to his own demise.

Paul has spent his entire life using his boyish charm and unthreatening lilt to conceal the deep cravenness that has made him the world’s most beloved rockstar.

“You’re an elderly billionaire, man,” I thought while I watched that Instagram Reel. “Why are you making phone videos in Tulsa fucking Oklahoma?”

It’s unfortunate (for me and the people around me) that I’ve formed a deeply unhealthy obsession with Paul McCartney since the release of the “Get Back” documentary in 2021. He is an avatar for how I view creativity. I will never relate to his high output or contentment with creating music that, even at his most experimental, hews to a formula.

I am a “John songs” guy (a thing you can no longer say because of woke). I’m an “All Things Must Pass” guy, too, because George’s bitterness charms me. Neither of them created much that I enjoy listening to after the dissolution of the Beatles. But frankly, I don’t care much about what any of these guys did once they were apart. We can see through all of their solo work that they were only revolutionaries when together.

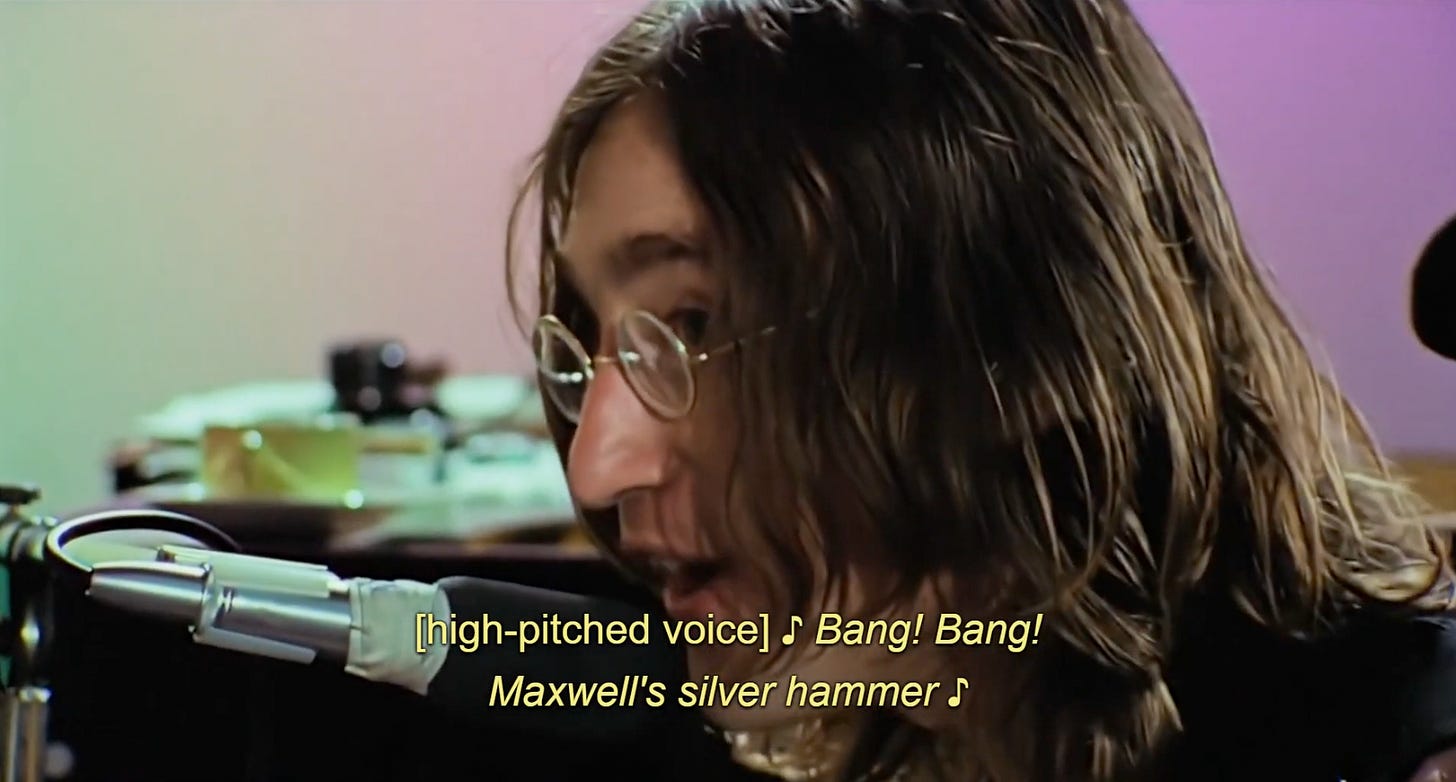

In “Get Back,” Paul’s chipper and charming facade starts to break as he belittles his bandmates through the creation of their final album. Yet, he also deserves massive credit for being the only member of the band who is still invested in their existence, output, and success. He spent far too long making his checked-out bandmates record “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” — but he correctly pointed out that someone had to be a leader after the death of their manager, Brian Epstein.

We got “Abbey Road” and “Let It Be” out of those final years. John and George were already deep into their own creative evolutions by that point. George loved the sitar; John had transferred his mom issues to Yoko. Paul was, as he was from the time he and John wrote songs about teenage crushes together, the one who kept the whole rickety train on the tracks.

For most of the Beatles’ existence, John was considered the leader. By the final days, the band belonged to Paul. It’s evident in the video footage and output from that time.

This manifested in the rift between Paul and John that would, let’s be real, never be healed. John wanted the band to be represented by Allen Klein, who was managing the Rolling Stones at the time. Paul wanted them to be represented by his soon-to-be in-laws. George and Ringo went with John.

One morning, after drinking a nitro cold brew, I made my friend listen to an hour-long monologue about the legal dispute initiated by Paul that broke up the Beatles.

“That’s how the Beatles broke up?” she asked me, finally finding something that was of relative interest to anyone other than myself. Here is more of Paul’s genius. Everyone knows the songs. Hardly anyone realized that the end came when Paul severed himself from the rest of the band.

Over the last few years, I’ve consumed so many books and videos and old news stories about the Beatles that I can tell you every tale Paul has ever told about the mythology of the Beatles, the way these stories have evolved as his bandmates and contemporaries have died — and the way they contrast with objective reporting about every breath the Fab Four took from the day John met Paul. He is (Paul voice) a bit of a phony, y’know?

Many of these books have been recommended (or loaned) to me by my friend Alex Shephard, who thinks my opinions on Paul are horseshit. We are Americans in our 30s. We share a variety of interests. Yet we argue about Paul McCartney nearly every day. We’re so obsessive about this that after many years of thinking that we can work it out, we’re publicizing our debate through a pair of essays.

Alex has written a beautiful and persuasive rebuttal to this piece here.

Paul’s sculpting of his and the Beatles’ image is right there between the lines In books and interviews. He spends a lot of time talking about Little Richard but not so much time giving credit to Stuart Sutcliffe (“Shtu” in Paulese), who was John’s original sidekick. Paul snaked Stu to claim second-in-command status. This occurred when they were a teenage novelty act in Germany.

Paul gives more credit to George now, though still in a miserably condescending tone that he can’t seem to shake. Everything George felt about Paul is sung on his solo song, “Wah Wah.” At this point, Paul will seemingly play nice with anyone left in the Beatles estate because they, too, have to sign off on whatever is left to profit off their intellectual property.

My inquiry into finding a Unified Paul has taught me a lot about accepting the complexities of people — especially ones with long, very public lives like his. I joke that I have spent years trying to determine if Paul is “good or bad,” but he is just Paul. He’s brilliant, he’s boring, he’s curious, he’s predictable, he’s a Shakespeare or a Mozart. He’s polite, he’s greedy. He was, most importantly, incredibly hot when he lived in Scotland in the 1970s. (He knows this, too. Look at his Instagram avatar.)

But Paul, the man who consumers and critics have spent 70 years clamoring for, will not leave us alone. None of this is enough for him. He’s touring American towns smaller (and economically less impactful) than the working-class town where he was raised. He’s pumping out documentaries every year — most of which are made up of the same clips of recycled material edited and framed to indicate novelty.

His new book, “WINGS: The Story of a Band on the Run” attempts to present his Other Band as a liberation from the Beatles. Yet, in the foreword of the book, he himself admits that his interest in Wings was reinvigorated because other people who were too young to remember the 1960s had asked him about it. Someone just realized there will always be a market for a book by Paul McCartney.

But it’s just incessant. “Get Back” was a massive success. Then, there’s the six-part Hulu documentary “McCartney 3,2,1.” It is delightful, but full of the same anecdotes he’s been telling since the days John — and later George — died. If you want the charming stories behind his (sorry) very obvious songs, it’s a great watch.

It continues in different mediums. A collection of photographs he took on his Pentax camera during his Beatles days has been on a global tour since 2023. There is also “The Lyrics,” the enormous compilation of Paul’s explanation of the meanings behind the songs he (and John and George) wrote.

Then, late last year, the mid-90s documentary “Anthology” was re-released. It’s an incisive, comprehensive look at the Beatles (because it includes interviews with the now-dead people who were there when the band was active). But once again, it is a new project made on recycled material.

Now, there’s a documentary version of Sir Paul’s book about Wings. It will be released in late February. I’ll watch it because Paul and I share one very important opinion: Linda was a god among mortals.

Ultimately, what are we allowed to know about the life of the greatest artist of my lifetime? Everything, apparently, as long as Paul gets creative control and a nice stiff paycheck.

There is something special about our continued exposure to a living legend. Generations of people around the world have had the opportunity to idolize Paul McCartney. But he has spent 70 years telling stories from the days he and John spent playing rudimentary instruments together in Liverpool — and he’s had nearly 25 years since George died to speak on behalf of the Beatles.

Ringo, the diplomat, has the right idea to stay out of it and collect the residuals, but since George died he’s largely removed himself from the Beatles narrative. He just shows up.

McCartney’s eventual death will devastate me. I love Paul, and much of the pessimism I feel toward him likely comes from the feeling that I can relate to John’s mercurial insanity and George’s navel-gazing search for himself.

But Paul’s death will also put a firm end to any further information about the creative alchemy that gave us the most revolutionary band of all time. It’s all interpretation from here on out. And in the end, Paul will get the last word. Until then, he’s keeping himself occupied by playing the hits and grabbing every last dollar.

This seems so ungenerous. Meanwhile Paul thinks so highly of you.

Wonderful piece. As a lifelong Beatles (and Paul) fan, agree 100%.